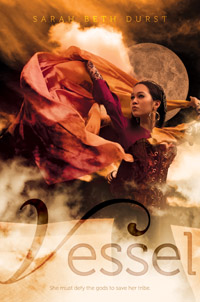

I got sidetracked at work and followed a link to the sample chapters of a new fantasy novel, Vessel, by Sarah Beth Durst.

The book is due next month from Simon & Schuster, which continues to impress me with the quality and quantity of their YA offerings.

The premise is compelling: What if you prepared your whole life to become a sacrifice to a goddess that would save your people, and then the goddess did not accept your sacrifice?

The sample reads very well. The pace is great, and the descriptions draw a solid world, full of textures, smells, sounds, and characters. I have small quibbles with the dialogue and the use of alliteration. Small quibbles indeed.

The protagonist is a girl, about 16 years old, and I think the crossover appeal to boys would be less than for The Hunger Games, but it's still possible. Then again, I'm not a teenage boy, so I don't mind.

The invitation that drew me in includes high praise from Tamora Pearce. If you're a fan of hers, as I am, this will certainly appeal.

Oh, and nice cover design.

About Me

- Steve Shea

- A 40-ish publisher (editor, project manager, etc.), husband, and father of an even number of offspring, I grew up, or failed to, reading fantasy and sci-fi. I still enjoy reading, and now am trying to write. My favorite books include YA fantasy, manga, biography, and advice to authors. I'm also a former history major/grad student/high school teacher and assessment writer. Now I work for a school supplement publisher, specializing in high-low chapter books. I spend a lot of my time controlling reading levels. At night, I cut loose and use long words. W00t!

Wednesday, August 29, 2012

Tuesday, August 21, 2012

Paolo Bacigalupi, SHIP BREAKER and THE DROWNED CITIES

Fans of the extreme physical action—violent, visceral, and

wrenching—of Suzanne Collins’ Hunger Games trilogy now have something in common

with fans of Philip K. Dick’s philosophical, alt-future ruminations about the

nature of humanity.

It’s a strange mix, but the way Paolo Bacigalupi does it, it

feels natural. The child protagonists of Ship Breaker and The Drowned Cities leave hooks deep in the willing reader. The world falls apart, and yet

the kids are still kids underneath their adaptation to their environment.

The natural environment is only the first of the changes

affecting the characters. In the wake of extreme climate change, the political

unity and economic base of the United States have vanished. Scavengers and

soldiers prey on the dead and the living, respectively. Bacigalupi writes child

protagonists entirely native to this post-apocalyptic world. They adapt or die,

and many die despite adapting. For the survivors, characteristics we think of

as childlike are a luxury that could get them killed.

Bacigalupi also introduces adults also shaped in varied ways

by the environment. Some are hard, cruel, and outwardly strong. Others are

kind, generous, and outwardly weak. There is a fairly strong valuation of adult

behaviors in Bacigalupi’s two books, but nothing so uninteresting as judgement.

The cruel, hard adults are neither excused flatly for their circumstances, or

blamed flatly for their actions. When doing right gets people killed, how are

we to judge those who do wrong to survive? There are distinctions—cruelty for

entertainment versus extreme violence for survival—that teenagers and adults

will be better able to parse than kids. These books are definitely for those

readers.

There’s an interesting structure to these books. Whereas

Collins’ Hunger Games trilogy has one protagonist and a fixed set of support

characters, Bacigalupi’s Drowned Cities trilogy (only 2/3 published with the

title book of the series coming second) has different protagonists in each of

the first two books.

At times, reading the second book, I felt that Nailer, the

protagonist of Ship Breaker, would show

up in a few pages. In a sense, he is the ideal companion of Malia, the second

book’s protagonist. Bacigalupi kept me anticipating his reappearance for most

of the book. However, Ship Breaker

shares only one character with the sequel, and the discovery was so unexpected,

I’ll leave it to readers to discover.

All of these characters—the culled and calloused children,

the scarred and scary adults, and the human-animal hybrids Bacigalupi

invents—explore some of the same ground where Philip K. Dick left tracks. What

counts as human? It’s not easy to answer. Like Dick, Bacigalupi leaves the

argument (for now) inconclusive. The answers aren’t simple, and having opened

the can of worms, the humans of Philip Dick’s worlds with their un-welf-aware

androids and diembodied intelligences, those of Bacigalupi’s with their hybrids

and “nasty, brutish, and short” lives imposed by constant war argue it out

inconclusively, through words and deeds.

Monday, August 6, 2012

A Happy Stumble: "No," by Brian Doyle

By unreproducible means, a work-related quest brought me almost all the way to this essay of remembrance and humor by a magazine editor. In "No," Brian Doyle offers a lovely, meandering, and brief apologia of editorial rejection. He packs it full of insight, weaves it close with experience, and draws it all through a gentle sense of humor. As an aspiring writer and sort of an editor, I caught a glimpse of the farther edges of these professions. Sir Isaac Newton's image of a boy playing with sea-shells comes to mind.

If you like to read words, these are worth reading.

If you like to read words, these are worth reading.

Thursday, August 2, 2012

Words about Mitt Romney

My mother posted a link to Thomas Friedman's editorial, "Why Not in Vegas" on Romney's trip to Israel. I was struck by the words and phrases Friedman associates with Romney and his trip. Here's the skip-through:

I think they may also have real-world effects. Among the effects Friedman is observing is the deterioration of peace, or of the potential for peace, in the Middle East when American politicians pander instead of speaking uncomfortable truths.

Another effect may be that Friedman finds himself severed from Movement conservatives. I may not have long to wait till he's branded a socialist.

- not about learning

- satisfy the political whims

- all about money anyway

- abase himself

- wrong with the U.S.-Israel relationship

- add more pandering

- canard

- had time for a $50,000-a-plate breakfast

- did not have two hours to go to Ramallah

- didn’t know what he was talking about

- feeding off this conflict for political gain

- using this conflict as a backdrop for campaign photo-ops and fund-raisers

- making things even worse

- grovel for Jewish votes and money

- blatantly ignoring the other side

- not going to do something constructive

I think they may also have real-world effects. Among the effects Friedman is observing is the deterioration of peace, or of the potential for peace, in the Middle East when American politicians pander instead of speaking uncomfortable truths.

Another effect may be that Friedman finds himself severed from Movement conservatives. I may not have long to wait till he's branded a socialist.

Wednesday, August 1, 2012

Revision vs. Original Work

At what point does my chapter-book revision become original work?

Black would be the color of text unedited since the last save. Only since the last save. And there's precious little of it. This screenshot it pretty representative.

Just wondering.

Black would be the color of text unedited since the last save. Only since the last save. And there's precious little of it. This screenshot it pretty representative.

Just wondering.

Where, indeed: Barry Deutsch's HEREVILLE: How Mirka Got Her Sword

Years ago now, I read a hefty online sample of Barry Deutsch's more-than-charming graphic novel Hereville: How Mirka Got Her Sword. I call it "more than charming" because it was both a fairy-tale-ish story told in drawings that, despite the muppetlike heads, seemed so obviously perfect for it, and at the same time a rich treatment of humanity.

Find out more from Deutch's website, Hereville.

I don't put it that way to make it seem grandiose, but the universality of the story, told from the perspective of a little slip of a girl in a tiny town that was part of an often-overlooked corner of a small minority in a big, pushy world, is hard to deny. Deutsch has created such a perfect character in Mirka that, although she is culturally atypical, and kind of an odd kid within her culture, a reader as unlike her as myself has no trouble sympathizing.

Mirka has a strict stepmother, a distant father, a nosy little brother, bullies and monsters to avoid, and a few things that she loves without restraint, an immediate kind of nostalgia that I think only children can feel. Certain things, often small or outwardly insignificant, are indispensable to kids, around the time that they become aware of the potential for change. Having lost her mother, Mirka treasures the familiar, and even though her lodestones are different from mine, they feel as true and real in the story as my own did (at least in nostalgic perspective).

Recently, I stumbled across the full book at the library, and snapped it up. My kids (11 and just-turned-8) tore through it and declared it was good. I snuck in two reads, with mounting satisfaction.

And what do I learn today? Happily, that there will soon be a second Hereville. Perfect.

Find out more from Deutch's website, Hereville.

I don't put it that way to make it seem grandiose, but the universality of the story, told from the perspective of a little slip of a girl in a tiny town that was part of an often-overlooked corner of a small minority in a big, pushy world, is hard to deny. Deutsch has created such a perfect character in Mirka that, although she is culturally atypical, and kind of an odd kid within her culture, a reader as unlike her as myself has no trouble sympathizing.

Mirka has a strict stepmother, a distant father, a nosy little brother, bullies and monsters to avoid, and a few things that she loves without restraint, an immediate kind of nostalgia that I think only children can feel. Certain things, often small or outwardly insignificant, are indispensable to kids, around the time that they become aware of the potential for change. Having lost her mother, Mirka treasures the familiar, and even though her lodestones are different from mine, they feel as true and real in the story as my own did (at least in nostalgic perspective).

Recently, I stumbled across the full book at the library, and snapped it up. My kids (11 and just-turned-8) tore through it and declared it was good. I snuck in two reads, with mounting satisfaction.

And what do I learn today? Happily, that there will soon be a second Hereville. Perfect.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)